Chris Barrett, a PR professional who is one of the few thousands beta testers of Google Glass, posted a video on YouTube on July 4, announcing, "This video is proof that Google Glass will change citizen journalism forever." The video, which Barrett shot on the boardwalk in Wildwood, New Jersey, features the tail end of a fist fight and the arrest of two participants by local police. Discussing the video with Venture Beat, Barrett explained the benefit of Google Glass in filming these events: "I think if I had a bigger camera there, the kid would probably have punched me. But I was able to capture the action with Glass and I didn't have to hold up a cell phone and press record."

Despite Barrett's fear of being assaulted, I noticed that many of the other witnesses of the fight also decided to film events with their phones, and none were menaced by the police or the brawlers. Google Glass, capable of surreptitiously recording video, is less a revolution than an extension of an existing trend: we all carry cameras and, when something out of the ordinary happens, we record it.

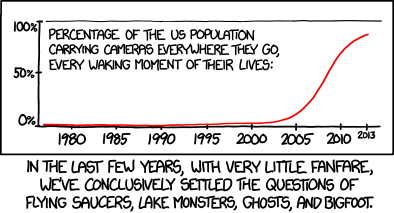

Randall Munroe, one of the Internet's most astute social commentators, has already thought through one of the key implications of pervasive cameras: if 10 million tourists with camera phones haven't photographed the Loch Ness Monster, we can probably finally declare it a myth. But the most thoughtful commentator on the implications of pervasive cameras is a man who's been wearing a camera for years: Steve Mann.

Dr. Steve Mann is a professor at the University of Toronto, an alum of the Media Lab, and a pioneer in the design of wearable computer systems. Since 1981, he has been building and wearing computer systems that can record what he sees, as well as superimpose computer-generated imagery on his field of vision. Mann has logged tens of thousands of hours wearing different generations of his EyeTap system, and has written eloquently about both how he uses the tool and how others react to him when he's wearing a camera.

Mann coined the term "sousveillance," watching from below, as an alternative to "surveillance," watching from above. When the UK government deploys 1.85 million cameras to monitor city streets, or the US government intercepts billions of communications, these powerful institutions send a message: consider yourself watched at all times and behave accordingly. Mann suggests that we might invert the paradigm by pointing the camera at institutions and authorities, reminding them that citizens are watching as well.

Compared to the power of monitoring all digital communications in a nation, the ability to film police making an arrest initially seems like weak tea. (Even asserting rights to this form of sousveillance has required protracted legal battles, and commentator Steve Silverman strongly discourages people from recording police surreptitiously, as Barrett did.) But protesters in the Occupy movement took to live-streaming video from their encampments, both to share proceedings with people who couldn't be physically present, and to ensure that any police violence would be documented and broadcast. (Charlie DeTar, a doctoral student at the Media Lab, produced a map visualizing these streams.) The firing of Lt. John Pike, the infamous "pepper-spray cop" who assaulted students at UC Davis, suggests that this documentation of abuse was effective.

Sousveillance has also become a routine part of election monitoring in much of the world. Enabled by technologies like Ushahidi, which allows thousands of people to report on an event and place their reports on an interactive map, citizen monitoring of elections by photographing long lines at polling places or voting irregularities has become common practice in much of the world.

When Barrett declares a revolution in citizen journalism due to Google Glass, he's thinking of this sense of sousveillance. With widespread use of Google Glass, it's more likely that abuses of power will be documented, as well as natural disasters and breaking news. But Barrett's video shows that there's a giant gap between an eyewitness account and a journalistic story. Yes, Barrett's video shows an arrest, but it doesn't help us figure out who was fighting and why, or what happened to the men after they were arrested. Pervasive cameras create more inputs for journalism, but they don't automatically answer the questions of who, what, where, and why that we expect of good journalism.

When Mann discusses sousveillance, he often talks about another facet of the idea: by wearing a camera and pointing it at people, he forces people to think about the implications of being watched. People often react badly to Mann's sousveillance, complaining that his camera is an invasion of their privacy. Mann hopes that this discomfort at being watched will inspire deeper consideration of the ways people are watched by corporations and governments.

Watching Barrett's video, it's easy to feel uncomfortable: for the people watching in the crowd who now feature in his film, and for the participants in the fight who've now been viewed by almost a million people online. Perhaps that discomfort will translate into a discussion of societal norms around cameras and lead to a legal or societal agreement that we don't record people without their permission—except in extraordinary circumstances.

There's another possibility. If Google Glass and other wearable cameras become pervasive, the uncomfortable and provocative experience of being watched eventually disappears and we simply get used to the idea that public spaces are spaces in which we expect to be filmed. Before we accede to that possibility, it's worth having an extended conversation about the balance between the power we gain from sousveillance and the constraints that surveillance puts on our behavior.

Ethan Zuckerman is director of the MIT Center for Civic Media.