Saturday, December 24, 2011

Tuesday, December 20, 2011

Welcome Sep Kamvar

I have great news.

We will be welcoming Sep Kamvar as the Media Lab's newest faculty member as of January 1, 2012. He will be joining us as the LG Associate Professor of Media Arts and Sciences, heading the Social Computing research group. He will be located in the East Lab, on the second floor of E14.

Sep comes to us from Stanford University, where he earned his PhD and is currently consulting assistant professor at the Institute for Computational and Mathematical Engineering. To date, his most significant contributions have been at the intersection of computer science and mathematics, particularly in the fields of personalized search and peer-to-peer networks. For four years, he took a leave from his graduate work to found a personalized search company, and then, when Google acquired the company, built and led Google’s engineering efforts in personalization. His artwork has been exhibited at The Museum of Modern Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum.

You can see the talk that Sep gave at the Fall meeting in October.

I'm really excited by Sep's research areas, his deep ties with Silicon Valley and the thoughtful, fresh and exciting energy that he brings. Yay!

We will be welcoming Sep Kamvar as the Media Lab's newest faculty member as of January 1, 2012. He will be joining us as the LG Associate Professor of Media Arts and Sciences, heading the Social Computing research group. He will be located in the East Lab, on the second floor of E14.

Sep comes to us from Stanford University, where he earned his PhD and is currently consulting assistant professor at the Institute for Computational and Mathematical Engineering. To date, his most significant contributions have been at the intersection of computer science and mathematics, particularly in the fields of personalized search and peer-to-peer networks. For four years, he took a leave from his graduate work to found a personalized search company, and then, when Google acquired the company, built and led Google’s engineering efforts in personalization. His artwork has been exhibited at The Museum of Modern Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum.

You can see the talk that Sep gave at the Fall meeting in October.

I'm really excited by Sep's research areas, his deep ties with Silicon Valley and the thoughtful, fresh and exciting energy that he brings. Yay!

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

How Does Society React When Technology Approaches Magic?

[Graduate student Matt Stempeck shares his notes from today's talk by frog design's Chief Creative Officer Mark Rolston.]

The audio fidelity on the #MediaLabTalk livestream wasn't great at first, so I attempted to liveblog. Unfortunately I had to head to class as the second speaker, Jared Ficklin, came on, but we'll be posting video shortly.

Mark Rolston, Chief Creative Officer of frog design, has been with frog for years and has seen the company grow to include strategy.

He believes that companies want to innovate, but that the need to scale and manage complicated supply chains impedes their ability to do so. Some companies are failing to simply build the most innovative product but even more so, to integrate with rest of the product ecosystem to design the entire customer experience.

Frog's experience in the 1980s associating an emotional, ephemeral experience with drinking Coke, which is essentially brown sugar water, has proven useful decades later in designing meaningful software interactions and making virtual experiences richer. (The slide showed a Classic Coca Cola bottle, not New Coke ;-)).

Science fiction has been great at predicting what's to come (by taking plenty of shots, complete with plenty of misses), but it's often been about better aligning ourselves with computers.

A slide shows how the cellphone has replaced So. Many. Functions.

Products like a crown, a scepter, a totem still have deep meaning beyond their physical use, haven't made the jump to digital experience yet.

Our experience with computing has gone something like this:

A slide shows the many parts (microphone, screen, processor) that go into a computer, and Mark suggests that computing has become and will continue becoming decoupled. Even the smallest, sleekest computer today will be surpassed by the decoupling of the concept of computing. Computers will not be composed, fixed assemblies of parts, but a set of possibilities between objects that are talking to one another. Computing will always be with you, and won't be something you carry, but rather a diffuse infrastructure.

The entire world is the platform. Mark makes the point that the city is the new computer. It's a contained but still open space of sensors and people and inputs, of network sensors and interfaces.

The challenge, and less obvious part, is now to move from the private computing experience we're used to into a shared experience. Even with digital sharing, consumer electronics have been designed for the individual. A diffuse computing environment inherently includes many people and common experiences.

Frog design took over every screen in Times Square for GE's World Health Day in 2007 with nothing but a PowerMac Pro in a closet and a VGA cable (at the technical level, at least). It was a nice early example of computing at scale, with thousands of people computing simultaneously.

Mark segues into the fact that we've always had a private life and a public life, and there's been relatively little bleed between the two. Sure, we wrote private letters that became public, but they were a relatively low-fidelity medium. But now the two lives are being tangled. Mark quotes Alfred Korzybski, saying, "The map is not the territory." The public image of us has not been an accurate representation of who we really are. But now our maps are becoming their own territory as our private lives go online in high fidelity.

We'll change as much as computing does, Mark says, with an emerging second brain, second life. We have augmented selves. [We can sign up to get knock knock jokes via text and everyone will think we're really funny].

Mark shows a product created years ago, which listens to your conversations and conducts intelligent web queries to augment your knowledge when someone asks you, for example, about the football game last night. They found that this technology itself drove the conversation in a new direction and dominated the original topic–the map overtook the territory. [I'd consider this a failure of the goals of an augmented technology–technology should blend in with our existing social interactions, not completely disrupt them].

Another form of knowledge augmentation is "decision support." Intel sponsored a display to help people pick out outfits at a department store. Again, the question of a shared, embedded computing experience rather than an individual, personal, outfit-selection tool brought up new questions.

One of the most exciting dynamics possible with augmented information is that it grants us new superpowers for social advantage. Ubiquitous computing can help us know more intellectually or socially or give us more basic social warmth. This brings up the question of what it means to know something. There's a difference between someone truly knowing your birthday vs. your Facebook friends "knowing" your birthday. The impending social ramifications can't be overstated.

Mark brings up the example of the film Up in the Air, where everyone in the airline industry, including computer systems, knows George Clooney with a level of false, commercial intimacy, and the movie makes a clear comment on this false life and the opportunity cost of Clooney's character missing out on real connection.

Mark confronted these questions of digitally enabled, real-time knowledge head on at a conference, where the organizers had given everyone a SpotMe tool. It lets you see everyone's name, title, background, and where in the room they are. You can literally go find people as if you have social sonar. The tool basically makes each of us a node in a network, and exposes all of the social information that's normally revealed via conversations and introductions. There are clearly strong benefits and drawbacks to such a tool.

Each of us has a variation of the human brain, and networking them normalizes our differences, to the point that only the loudest obnoxious voices online cause a spike (with implications for our politics).

Handing over agency to a machine requires a level of trust. Mark shows a great video clip of TED attendees taking one of Google's self-driving cars for a spin for the first time. Almost everyone has a freakout moment as the car speeds around and steers itself. It makes us uncomfortable and we question handing over agency to computers/robots.

Frog found this out firsthand when they designed medical devices and pill reminders. Mark says that statistics show that doctors regularly give incorrect advice but are pretty well protected in doing so by the legal system. But a much, much more accurate digital device suffers a much worse fate when it occasionally dispenses the wrong advice. Suing a computer is apparently much easier than suing a doctor. If we allow the Siris of the world to take the next step in intelligence, from dictating existing information to actually making original recommendations, we're going to have to deal with the social and legal ramifications.

Mark thinks one of the terms were going to need to use in a better way is 'magic,' when computing objects escape their mechanical origins and pick up more of the ephemeral. The word 'magic' has historically been owned by charlatans and zealots, but we're going to have to build a new vocabulary of the high mind to take into account our new affordances.

[And, according to event attendee Dan Novy, "The Object-Based Media Group regularly uses the term "Magic" to describe what our goals and design philosophies are."]

Matt Stempeck is a first-year graduate student at the Media Lab / Center for Civic Media.

The audio fidelity on the #MediaLabTalk livestream wasn't great at first, so I attempted to liveblog. Unfortunately I had to head to class as the second speaker, Jared Ficklin, came on, but we'll be posting video shortly.

Mark Rolston, Chief Creative Officer of frog design, has been with frog for years and has seen the company grow to include strategy.

He believes that companies want to innovate, but that the need to scale and manage complicated supply chains impedes their ability to do so. Some companies are failing to simply build the most innovative product but even more so, to integrate with rest of the product ecosystem to design the entire customer experience.

Frog's experience in the 1980s associating an emotional, ephemeral experience with drinking Coke, which is essentially brown sugar water, has proven useful decades later in designing meaningful software interactions and making virtual experiences richer. (The slide showed a Classic Coca Cola bottle, not New Coke ;-)).

Science fiction has been great at predicting what's to come (by taking plenty of shots, complete with plenty of misses), but it's often been about better aligning ourselves with computers.

A slide shows how the cellphone has replaced So. Many. Functions.

Products like a crown, a scepter, a totem still have deep meaning beyond their physical use, haven't made the jump to digital experience yet.

Our experience with computing has gone something like this:

- First wave: Users are operators, like operators of heavy equipment, without a real connection to the data

- Second wave: Slide shows an iPhone. More personal relationship, we carry it with us; we're babysitters

- Third wave: Slide shows humorously early wearable technology from the Media Lab. The third wave's going to look more like Hal, and consume your entire environment, an invisible layer when you're doing something else like cooking, bathing.

A slide shows the many parts (microphone, screen, processor) that go into a computer, and Mark suggests that computing has become and will continue becoming decoupled. Even the smallest, sleekest computer today will be surpassed by the decoupling of the concept of computing. Computers will not be composed, fixed assemblies of parts, but a set of possibilities between objects that are talking to one another. Computing will always be with you, and won't be something you carry, but rather a diffuse infrastructure.

The entire world is the platform. Mark makes the point that the city is the new computer. It's a contained but still open space of sensors and people and inputs, of network sensors and interfaces.

The challenge, and less obvious part, is now to move from the private computing experience we're used to into a shared experience. Even with digital sharing, consumer electronics have been designed for the individual. A diffuse computing environment inherently includes many people and common experiences.

Frog design took over every screen in Times Square for GE's World Health Day in 2007 with nothing but a PowerMac Pro in a closet and a VGA cable (at the technical level, at least). It was a nice early example of computing at scale, with thousands of people computing simultaneously.

Mark segues into the fact that we've always had a private life and a public life, and there's been relatively little bleed between the two. Sure, we wrote private letters that became public, but they were a relatively low-fidelity medium. But now the two lives are being tangled. Mark quotes Alfred Korzybski, saying, "The map is not the territory." The public image of us has not been an accurate representation of who we really are. But now our maps are becoming their own territory as our private lives go online in high fidelity.

We'll change as much as computing does, Mark says, with an emerging second brain, second life. We have augmented selves. [We can sign up to get knock knock jokes via text and everyone will think we're really funny].

Mark shows a product created years ago, which listens to your conversations and conducts intelligent web queries to augment your knowledge when someone asks you, for example, about the football game last night. They found that this technology itself drove the conversation in a new direction and dominated the original topic–the map overtook the territory. [I'd consider this a failure of the goals of an augmented technology–technology should blend in with our existing social interactions, not completely disrupt them].

Another form of knowledge augmentation is "decision support." Intel sponsored a display to help people pick out outfits at a department store. Again, the question of a shared, embedded computing experience rather than an individual, personal, outfit-selection tool brought up new questions.

One of the most exciting dynamics possible with augmented information is that it grants us new superpowers for social advantage. Ubiquitous computing can help us know more intellectually or socially or give us more basic social warmth. This brings up the question of what it means to know something. There's a difference between someone truly knowing your birthday vs. your Facebook friends "knowing" your birthday. The impending social ramifications can't be overstated.

Mark brings up the example of the film Up in the Air, where everyone in the airline industry, including computer systems, knows George Clooney with a level of false, commercial intimacy, and the movie makes a clear comment on this false life and the opportunity cost of Clooney's character missing out on real connection.

Mark confronted these questions of digitally enabled, real-time knowledge head on at a conference, where the organizers had given everyone a SpotMe tool. It lets you see everyone's name, title, background, and where in the room they are. You can literally go find people as if you have social sonar. The tool basically makes each of us a node in a network, and exposes all of the social information that's normally revealed via conversations and introductions. There are clearly strong benefits and drawbacks to such a tool.

Each of us has a variation of the human brain, and networking them normalizes our differences, to the point that only the loudest obnoxious voices online cause a spike (with implications for our politics).

Handing over agency to a machine requires a level of trust. Mark shows a great video clip of TED attendees taking one of Google's self-driving cars for a spin for the first time. Almost everyone has a freakout moment as the car speeds around and steers itself. It makes us uncomfortable and we question handing over agency to computers/robots.

Frog found this out firsthand when they designed medical devices and pill reminders. Mark says that statistics show that doctors regularly give incorrect advice but are pretty well protected in doing so by the legal system. But a much, much more accurate digital device suffers a much worse fate when it occasionally dispenses the wrong advice. Suing a computer is apparently much easier than suing a doctor. If we allow the Siris of the world to take the next step in intelligence, from dictating existing information to actually making original recommendations, we're going to have to deal with the social and legal ramifications.

Mark thinks one of the terms were going to need to use in a better way is 'magic,' when computing objects escape their mechanical origins and pick up more of the ephemeral. The word 'magic' has historically been owned by charlatans and zealots, but we're going to have to build a new vocabulary of the high mind to take into account our new affordances.

[And, according to event attendee Dan Novy, "The Object-Based Media Group regularly uses the term "Magic" to describe what our goals and design philosophies are."]

Matt Stempeck is a first-year graduate student at the Media Lab / Center for Civic Media.

Thursday, November 17, 2011

Media, Freedom, and the Web: Civic Media at the Mozilla Festival

The Mozilla Festival on Media, Freedom, and the Web (Nov 4-6, hashtag #mozfest) was three days in London of "less yack, more hack" focused on journalism and media technologies. The attendees brought together a great convergence of organizations that care about journalism, media, social good, education, open platforms, and web technologies. The weekend held a rich schedule of design challenges, learning labs, and fireside chats, offering everyone opportunities to meet, plan, make, and reflect on media and the web.

The overall conference theme centered on protecting and nourishing a read/write web. During the final event, speakers emphasized the importance of supporting technology and cultures that people around the world can use to make content, tools, and games, rather than simply consume them. There was a general sense that beautiful but confined “walled gardens” and closed technologies diminish the open web–and, by extension, innovation. To preserve the open spirit and capabilities that flourish on the Internet, we must protect the ability to do things like view source code, remix content, and more generally learn how to make.

During the festival, the Mozilla and Knight Foundations announced the 2011/12 Knight Mozilla News Technology Fellows, including the Media Lab's very own Dan Schultz. The Knight Mozilla fellowships form an exciting open innovation initiative: fellows will be embedded software developers at Al Jazeera, the BBC, The Boston Globe, the Guardian, and Zeit Online. As they make technologies for their own news outlets, the fellows will also collaborate with each other to develop open-source technologies to advance the future of news.

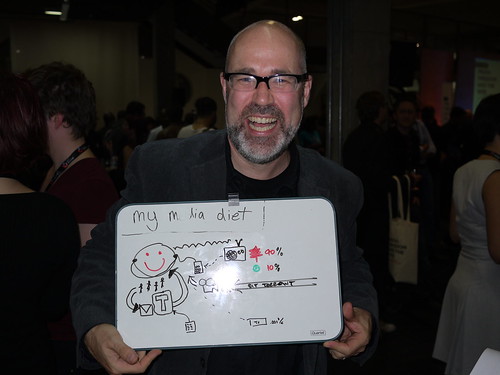

Matt Stempeck and I went to the festival to collect ideas for an exciting new project at the Center for Civic Media: technology to track your media diet. Led by our director Ethan Zuckerman, this project will track the content that media organizations and bloggers publish over time, as well as allow consumers to set goals for their own media consumption (Ethan spoke about this at the Lab's fall 2011 meeting). At the Mozilla Festival, we asked journalists, film-makers, and developers to draw their media diet, and held a design discussion about nutritional labels for the news. I love the smiley face on Mozilla Foundation executive director Mark Surman's media diet. Mark also taught me a new word to use when praising others: lovebombs.

Lovebombs (noun, plural)

Example: "Major lovebombs to Michelle Thorne, Mozilla and Knight for a great conference!"

Matt Stempeck and some new friends

Mozilla Foundation Executive Director Mark Surman's media diet

My favorite part of the Festival was the Hive London Popup for Teens, a series of sessions bringing together youth education organizations from across America and Europe. Instead of just talking with each other, we learned from each other by teaching young people in the same open space. I brought along Aago, a Center for Civic Media project for youth media production. I also had a lovely time introducing young people to Scratch. Before joining the Media Lab this year, I helped found a creative writing center in London, so it was fun to work with London teenagers once more!

Overall I had a wonderful time at the Mozilla Festival. We met some great civic organizations, hacking and yacking with a fascinating range of people. The Knight Foundation funds the Center for Civic Media, and I really enjoyed meeting people within the Knight-Mozilla circle.

The UK was my home for 5 years until I left London in July to join the Media Lab. I admit I felt wistful as I walked the streets I love so well. But surrounded by my new Media Lab colleagues, in the company of the exciting innovators at the Mozilla Festival, I am excited and inspired about what we can do together for media, freedom, and the web.

Here’s more:

Civic Media

"Civic Media Goes to London, Part One"

"Putting Voldemort into the Guardian: Remixing the News with Hackasaurus"

"Designing a Nutritional Label for the News at the Mozilla Festival"

"Discussion with Bilal Randeree on Liveblogging at Al Jazeera"

Nieman Lab

"Ethan Zuckerman Wants You To Eat Your News Vegetables"

"How Social Guilt can Change Our Media Habits or Just Make Us Lie About Them"

"Lessons from the Mozilla Festival: How the Knight and Mozilla Foundations are Thinking about Open Source"

Mozilla Knight News Tech Fellow Laurian Gridinoc: "Visualising my News Diet"

Knight Foundation

Knight News Challenge 2012 Preview

Highlights from the Mozilla Festival

Nathan Matias: "Technology Tent, Occupy London"

Open Knowledge Foundation: "Hacks and Hackers Gather to Write the First Data Journalism Handbook"

J. Nathan Matias is a first-year graduate student researching media consumption, creative learning, and community co-design at the Center for Civic Media.

Matt Stempeck is a first-year graduate student researching political identity and how people change their minds, at the Center for Civic Media.

Dan Schultz is a second-year graduate student in the Information Ecology group and the Center for Civic Media, researching tools to help people consume information more carefully.

Friday, October 28, 2011

Networks Understanding Networks: Fall Event Followup

Thanks again to my co-host César Hidalgo and everyone who helped organize and participated in the Fall Media Lab event Networks Understanding Networks—my first meeting. I was very inspired by the energy and the sense of community and I hope you felt the same. While we’re still energized from the experience and great interactions, we’re already thinking about how to make improvements for next spring’s meeting. Please email any thoughts or feedback you might have to meeting-feedback@media.mit.edu.

Both César and I agree that one of the most important messages that we imparted in two jam-packed days was the benefit of offering a meeting that is highly participatory and inclusive of all of the participants. We firmly believe that great ideas come from encouraging all attendees to talk to lots of different people about topics of greatest interest to them and their organizations. We hope that the meetings are both the source of great new ideas as well as a way to share our ideas. We will continue to look for new and engaging formats to maximize these opportunities. For this meeting we focused on unconferences and research open houses. We’ll be refining these for next year, as well as adding new formats for interaction.

And as part of the Lab’s new focus on openness, for the first time we offered all the meeting’s presentations to the world by live streaming them on the web in real time. These are archived and available for viewing (http://www.media.mit.edu/events/fall11/networks).

Keynote speakers included: Albert-Lászió Barabási, on human dynamics; Nicholas A. Christakis, on the evolutionary significance of human social networks; and Ricardo Hausmann, on what countries know about what they produce and why it matters. Other talks were by Ethan Zuckerman, on understanding media as an ecosystem; Sep Kamvar, on search and the social web; and the Media Lab’s Ed Boyden, Kent Larson, John Moore, Neri Oxman, and Sandy Pentland. You can also view a panel discussion on open innovation and creativity that included Larry Lessig, John Seely Brown, Yochai Benkler, Chris DiBona, and me. The closing remarks by Wadah Khanfar, who until recently was the director general of the Al Jazeera Network, were presented via Skype, which unfortunately created some quality issues for viewing,

Take a look and listen, (http://www.media.mit.edu/events/fall11/networks), and let us know what you think.

- Joi

Both César and I agree that one of the most important messages that we imparted in two jam-packed days was the benefit of offering a meeting that is highly participatory and inclusive of all of the participants. We firmly believe that great ideas come from encouraging all attendees to talk to lots of different people about topics of greatest interest to them and their organizations. We hope that the meetings are both the source of great new ideas as well as a way to share our ideas. We will continue to look for new and engaging formats to maximize these opportunities. For this meeting we focused on unconferences and research open houses. We’ll be refining these for next year, as well as adding new formats for interaction.

And as part of the Lab’s new focus on openness, for the first time we offered all the meeting’s presentations to the world by live streaming them on the web in real time. These are archived and available for viewing (http://www.media.mit.edu/events/fall11/networks).

Keynote speakers included: Albert-Lászió Barabási, on human dynamics; Nicholas A. Christakis, on the evolutionary significance of human social networks; and Ricardo Hausmann, on what countries know about what they produce and why it matters. Other talks were by Ethan Zuckerman, on understanding media as an ecosystem; Sep Kamvar, on search and the social web; and the Media Lab’s Ed Boyden, Kent Larson, John Moore, Neri Oxman, and Sandy Pentland. You can also view a panel discussion on open innovation and creativity that included Larry Lessig, John Seely Brown, Yochai Benkler, Chris DiBona, and me. The closing remarks by Wadah Khanfar, who until recently was the director general of the Al Jazeera Network, were presented via Skype, which unfortunately created some quality issues for viewing,

Take a look and listen, (http://www.media.mit.edu/events/fall11/networks), and let us know what you think.

- Joi

Friday, October 7, 2011

The Cognitive Limit of Organizations

This is a slide that I got from Cesar Hidalgo. He used this slide to explain a concept that I think is key to the way we think about how the Media Lab is evolving.

This is a slide that I got from Cesar Hidalgo. He used this slide to explain a concept that I think is key to the way we think about how the Media Lab is evolving.The vertical axis of this slide represents the total stock of information in the world. The horizontal axis represents time.

In the early days, life was simple. We did important things like make spears and arrowheads. The amount of knowledge needed to make these items, however, was small enough that a single person could master their production. There was no need for a large division of labor and new knowledge was extremely precious. If you got new knowledge, you did not want to share it. After all, in a world where most knowledge can fit in someone's head, stealing ideas is easy, and appropriating the value of the ideas you generate is hard.

At some point, however, the amount of knowledge required to make things began to exceed the cognitive limit of a single human being. Things could only be done in teams, and sharing information among team members was required to build these complex items. Organizations were born as our social skills began to compensate for our limited cognitive skills. Society, however, kept on accruing more and more knowledge, and the cognitive limit of organizations, just like that of the spearmaker, was ultimately reached.

When the Media Lab was founded 25 years ago, many products were still single-company products and most, if not all, of the intellectual property was contained in a single company. Today, however, most products are combinations of knowledge and intellectual property that resides in different organizations. Our world is less and less about the single pieces of intellectual property and more and more about the networks that help connect these pieces. The total stock of information used in these ecosystems exceeds the capacity of single organizations because doubling the size of huge organizations does not double the capacity of that organization to hold knowledge and put it into productive use.

In a world in which implementing the next generation of ideas will increasingly require pulling resources from different organizations, barriers to collaboration will be a crucial constraint limiting the development of firms. Agility, context, and a strong network are becoming the survival traits where assets, control, and power used to rule. John Seely Brown refers to this as the "Power of Pull."

The Media Lab and its members need to adapt to this world by focusing on creating a platform that can help all of us navigate this new landscape. Together, we are more likely to find niches in the complex and dynamic industrial ecosystem of the 20th century. Openness and engagement will be key in this journey.

Saturday, September 24, 2011

Ganging Up on Cyberbullying

This week, 14-year-old Jamey Rodemeyer from New York ended his life after being persistently bullied on a social networking website. Despite talking about being bullied and asking for help repeatedly, nobody did anything to comfort him. And so when nobody seemed to acknowledge or care about his pain, he tragically ended his life. Every time I’ve thought about this story, I’ve felt a range of emotions, from chills and sadness to outright anger and disgust that nothing was done to help Jamey.

The scourge of cyberbullying has increased alarmingly over the past couple of years. Defined as the use of communication technologies for “persistent and repeated” harassment of individuals, cyberbullying magnifies the effects of traditional bullying. The fact that many cases involving adolescent cyberbullying have ended with tragic outcomes like suicides underlines the grave nature of this menace. There has been national and international recognition of the hazards of cyberbullying at the highest echelons of power, from the White House to the British House of Commons.

Just like spam once threatened the viability of email, cyberbullying now casts a dark shadow over social networking websites. Most of the current work focused on cyberbullying involves surveys to gauge its prevalence and awareness campaigns led by parents and school administrators. While these approaches have their place, there has been very little use of technology to tackle this problem.

Last fall, after watching a segment on cyberbullying by CNN’s Anderson Cooper, I began to wonder if there were any efforts to use computational linguistics to help detect textual cyberbullying on social networking websites. My thoughts found immediate and strong support from a fellow graduate student, Birago Jones, and my Media Lab advisors, Dr. Henry Lieberman and Professor Rosalind Picard. We decided to pry further into this topic. We were perplexed to discover that next to nothing was being done in the field of computational linguistics to tackle this problem. The more deeply we thought about it, the clearer it became that a technical approach to tackling cyberbullying on social networks would have to be a combination of computational linguistics for effective detection and reflective user interaction techniques for changing user behavior.

Since that time, we have been lucky to work with a couple of social networking websites and with other collaborators from both within and beyond the Media Lab. This past March, we were invited to the White House to participate on a national summit on tackling bullying led by the President and First Lady, where a collaboration between the Media Lab and the social networking website Formspring was announced. Since that time, the White House has connected us to MTV, with whom we are now collaborating. This week, the Department of Education held a follow-up summit where Secretary of Education Arne Duncan announced that MTV, in partnership with the MIT Media Lab, is opening the corpus of teenage stories on subjects related to cyberbullying for the wider research community at the website athinline.org.

In a world where applied natural language processing and user interaction design tend to revolve around commercial applications, precious little is being done on tackling this very serious social problem. We are so excited here at the Media Lab to draw from varied disciplines such as psycholinguistics, affective computing, adolescent psychology, sociology and then apply it to exert the full power and weight of natural language processing, machine learning, and human-computer interaction to develop a practical and empathetic solution that social networking websites can actually implement. And we find this work to be deeply inspiring.

Karthik Dinakar is a second-year graduate student researching applied natural language processing and machine learning in the Software Agents group

Birago Jones is a second-year graduate student researching reflective user interaction in the Software Agents group

Henry Lieberman is a Principal Research Scientist and director of the Software Agents group

Rosalind Picard is Professor of Media Arts and Sciences and heads the Affective Computing group

Wednesday, September 14, 2011

Social Computing at the Media Lab

Online Communities

As part of my research at the Media Lab, I have explored how the social and technical infrastructure of online communities contribute to their successes and failures. I am fascinated by the culture that emerges out of these online spaces. I have been doing this work in the Scratch Online Community, a website I developed with my colleagues in the Lifelong Kindergarten group, where close to one million children from around the world have created, shared, and remixed more than two million animations and video games.

More recently, I've started to study other online communities as well. This summer, as part of a Media Lab-CSAIL student collaboration, we published a study on the role of online anonymity and ephemerality in a large and controversial discussion board. Like many others, I've been intrigued by the intersection of social media and civic engagement. Recently I wrote a short piece that examines the use of social media in the continuing drug war in Mexico. The original blog post, titled Shouting Fire in a Crowded Hashtag was later republished on ReadWriteWeb, which attracted some interest. Here are some of the highlights.

Shouting Fire in a Crowded Hashtag

One of the many casualties of Mexico's continuing violence has been freedom of the press. The local media are caught in a battle between censorship and control from both drug cartels and local governments. Some newspapers, in order to stay safe, have officially announced a policy of self-censorship when it comes to reporting drug war-related news. Because the mainstream media can no longer fulfill its role of informing citizens, people have turned to social media. Last year I started to collect tweets related to the Mexican violence. I decided to do some simple word-count analysis in one of the data sets, and found how people follow a hashtag or keyword to report warnings and request confirmation from others about shootings in various parts of the cities affected by the violence. In several cities, these hashtags have emerged as a shared news resource where many people contribute what they see and hear to help one another. I also found how a handful of often anonymous people have become reliable information hubs that send and receive thousands of messages from other citizens. Twitter has now become one of the primary sources of citizen-driven news in Mexico. Many people don't leave work or home before checking Twitter to know which areas to avoid. Having this information can actually save people's lives.

While I was doing this analysis, rumors broke out on Twitter among users in the Mexican city of Veracruz: children were being kidnapped by one of the drug cartels. The governor dismissed the rumors on his Twitter account, but by then the city had already turned into chaos. Parents in panic left work to get their children from school, causing massive traffic jams, and there was generalized panic. It is still unclear what actually happened that day, but the official version is that the rumor was completely false. The government filed terrorism charges against 16 of the Twitter users that spread the rumor. Three of them are now in jail facing sentences of up to 30 years. The Mexican Twittersphere and organizations like Amnesty International have voiced concerns on the excessive use of power.

Where does the Media Lab fit in all this?

I think this particular case of the role of social media in the Mexican drug war emphasizes some of the many challenges and promises of social technologies. As these social computing systems permeate most spheres of life–from education, to civic engagement, to entertainment, to science–the role of technology designers goes beyond any traditional discipline. This is why I think the Media Lab is in a privileged position to have a big impact in this area. Beginning with the work of Judith Donath in the 1990s, the Lab already has a long history of research in this area.

As my time at the Lab is coming to an end, I am excited to see people like César Hidalgo, Sep Kamvar, and Ethan Zuckerman join the faculty and continue this work by approaching this complex and exciting research area with interesting and different perspectives. This work requires a diversity of approaches, from building systems to studying them and their social impact. I look forward to seeing where this work goes over the next few years.

Andrés Monroy-Hernández is finishing his PhD at the MIT Media Lab. You can follow him on Twitter.

As part of my research at the Media Lab, I have explored how the social and technical infrastructure of online communities contribute to their successes and failures. I am fascinated by the culture that emerges out of these online spaces. I have been doing this work in the Scratch Online Community, a website I developed with my colleagues in the Lifelong Kindergarten group, where close to one million children from around the world have created, shared, and remixed more than two million animations and video games.

More recently, I've started to study other online communities as well. This summer, as part of a Media Lab-CSAIL student collaboration, we published a study on the role of online anonymity and ephemerality in a large and controversial discussion board. Like many others, I've been intrigued by the intersection of social media and civic engagement. Recently I wrote a short piece that examines the use of social media in the continuing drug war in Mexico. The original blog post, titled Shouting Fire in a Crowded Hashtag was later republished on ReadWriteWeb, which attracted some interest. Here are some of the highlights.

Shouting Fire in a Crowded Hashtag

One of the many casualties of Mexico's continuing violence has been freedom of the press. The local media are caught in a battle between censorship and control from both drug cartels and local governments. Some newspapers, in order to stay safe, have officially announced a policy of self-censorship when it comes to reporting drug war-related news. Because the mainstream media can no longer fulfill its role of informing citizens, people have turned to social media. Last year I started to collect tweets related to the Mexican violence. I decided to do some simple word-count analysis in one of the data sets, and found how people follow a hashtag or keyword to report warnings and request confirmation from others about shootings in various parts of the cities affected by the violence. In several cities, these hashtags have emerged as a shared news resource where many people contribute what they see and hear to help one another. I also found how a handful of often anonymous people have become reliable information hubs that send and receive thousands of messages from other citizens. Twitter has now become one of the primary sources of citizen-driven news in Mexico. Many people don't leave work or home before checking Twitter to know which areas to avoid. Having this information can actually save people's lives.

While I was doing this analysis, rumors broke out on Twitter among users in the Mexican city of Veracruz: children were being kidnapped by one of the drug cartels. The governor dismissed the rumors on his Twitter account, but by then the city had already turned into chaos. Parents in panic left work to get their children from school, causing massive traffic jams, and there was generalized panic. It is still unclear what actually happened that day, but the official version is that the rumor was completely false. The government filed terrorism charges against 16 of the Twitter users that spread the rumor. Three of them are now in jail facing sentences of up to 30 years. The Mexican Twittersphere and organizations like Amnesty International have voiced concerns on the excessive use of power.

Where does the Media Lab fit in all this?

I think this particular case of the role of social media in the Mexican drug war emphasizes some of the many challenges and promises of social technologies. As these social computing systems permeate most spheres of life–from education, to civic engagement, to entertainment, to science–the role of technology designers goes beyond any traditional discipline. This is why I think the Media Lab is in a privileged position to have a big impact in this area. Beginning with the work of Judith Donath in the 1990s, the Lab already has a long history of research in this area.

As my time at the Lab is coming to an end, I am excited to see people like César Hidalgo, Sep Kamvar, and Ethan Zuckerman join the faculty and continue this work by approaching this complex and exciting research area with interesting and different perspectives. This work requires a diversity of approaches, from building systems to studying them and their social impact. I look forward to seeing where this work goes over the next few years.

Andrés Monroy-Hernández is finishing his PhD at the MIT Media Lab. You can follow him on Twitter.

Labels:

civic media,

mexico,

people,

scratch,

social computing,

social media,

twitter

Location:

75 Amherst St, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA

Sunday, September 4, 2011

Media Lab "Members" instead of "Sponsors"

One of the most important things I’m focusing on is the Media Lab’s relationship with our sponsors. Having worked with sponsors, and having fundraised for a variety of organizations, I believe the best relationships are those that are not purely transactional. When the relationship is based primarily on financial support, this sometimes causes strange power relationships and limits the field of exploration. Rather, I like working closely with funders/sponsors/members on a shared mission–exchanging ideas, coming up with new ideas, and building things together.

I want to get away from the idea that a sponsor is paying money for someone else to be smart, interesting, or productive. I believe that we really need to build a community–a kind of "tribe." To better convey this, from now on I'm going to start calling the companies that support the Media Lab "members" instead of "sponsors." Membership will not primarily be about financial support, but rather about the wisdom, inspiration, and reach these member companies can offer. It will also be about how they can enhance our ability to pursue our vision and impact the world. We will look for members who wish to join our community as active participants and contributors.

As part of pushing the Media Lab to be more of a platform than a container, the other thing that the Lab can do is help our members work with each other to create and participate in ecosystems of services, products, ideas, culture, and policies. I think it's essential in today's environment to think about ourselves more as a network, and I believe "members" helps convey this.

I want to get away from the idea that a sponsor is paying money for someone else to be smart, interesting, or productive. I believe that we really need to build a community–a kind of "tribe." To better convey this, from now on I'm going to start calling the companies that support the Media Lab "members" instead of "sponsors." Membership will not primarily be about financial support, but rather about the wisdom, inspiration, and reach these member companies can offer. It will also be about how they can enhance our ability to pursue our vision and impact the world. We will look for members who wish to join our community as active participants and contributors.

As part of pushing the Media Lab to be more of a platform than a container, the other thing that the Lab can do is help our members work with each other to create and participate in ecosystems of services, products, ideas, culture, and policies. I think it's essential in today's environment to think about ourselves more as a network, and I believe "members" helps convey this.

Saturday, September 3, 2011

Welcome New Media Lab Students: Two Cents from a Current Student

This week marked perhaps the most important annual event at the Media Lab: our welcoming a new batch of students, an event that infuses new blood and talent into the Lab’s 24 research groups.

I met many of the new students earlier this year, in April, when they were here for their 'preview event,' and it was really nice to see them again. It seems like only yesterday that I spent my first day at the Media Lab, and I cannot fathom how quickly time has gone by. As I enter my second year, listening to the new students has forced to me reflect on my own experience here.

On our very first day, we visited every research group at the Lab to learn a little about what they were working on and how we might get involved. I was nervous and excited at the same time. Nervous because everyone I met seemed to be so intelligent. Excited because of the sense of creativity and the aura of coolness.

And what a year it has been! I’ve interacted with some of the most brilliant and thought-provoking academic stalwarts of our times. I've met with CEO's and executives from many influential companies. I've even been fortunate enough to have been invited to the White House.

For those just coming to the Lab this week, I want to tell you that you certainly will experience many ups and downs during your time at MIT. But overall, to borrow an oft-used American phrase, “You’re in for one heck of a ride.” And remember….

1. Feel proud and don't be intimidated

You did not arrive here by accident, and no matter how modest you might be, you must be very talented and gifted. You've been chosen from hundreds of smart people, and you deserve to be here.

2. Meet the polymaths

I've always been a huge fan of Albus Dumbledore and Gandalf. If you've ever felt that you wanted to meet a real-world similarity, it’s you’re in luck. You will, from time to time, watch many polymaths ambling through the Lab when you least expect it. Marvin Minsky, the father of modern AI is perhaps the most famous polymath here, but there are many others: Henry Lieberman invented garbage collection in programming languages, and is a pioneer in intelligent user interfaces. Rosalind Picard invented affective computing, and is a leader in autism theory and technology. Mitchel Resnick was involved in the creation of LOGO for kids, but is also a leader in inventing tools to the meet the information needs of information communities. Every PI here has deep expertise in at least a couple of fields.

3. You and yours only

In the Media Lab, there are no required courses, and no established curriculum. You can choose and pick any course offered through the Lab’s academic Program in Media Arts, other MIT departments, or even Harvard. Choosing what course to take is a bit like being a kid in a candy shop. My heuristic has always been this: take a course if it you need it for your research, and always attempt to write a conference-quality paper at the end of it. For me, this has resulted in some very long-lasting collaborations with other groups at the Lab.

I met many of the new students earlier this year, in April, when they were here for their 'preview event,' and it was really nice to see them again. It seems like only yesterday that I spent my first day at the Media Lab, and I cannot fathom how quickly time has gone by. As I enter my second year, listening to the new students has forced to me reflect on my own experience here.

On our very first day, we visited every research group at the Lab to learn a little about what they were working on and how we might get involved. I was nervous and excited at the same time. Nervous because everyone I met seemed to be so intelligent. Excited because of the sense of creativity and the aura of coolness.

And what a year it has been! I’ve interacted with some of the most brilliant and thought-provoking academic stalwarts of our times. I've met with CEO's and executives from many influential companies. I've even been fortunate enough to have been invited to the White House.

For those just coming to the Lab this week, I want to tell you that you certainly will experience many ups and downs during your time at MIT. But overall, to borrow an oft-used American phrase, “You’re in for one heck of a ride.” And remember….

1. Feel proud and don't be intimidated

You did not arrive here by accident, and no matter how modest you might be, you must be very talented and gifted. You've been chosen from hundreds of smart people, and you deserve to be here.

2. Meet the polymaths

I've always been a huge fan of Albus Dumbledore and Gandalf. If you've ever felt that you wanted to meet a real-world similarity, it’s you’re in luck. You will, from time to time, watch many polymaths ambling through the Lab when you least expect it. Marvin Minsky, the father of modern AI is perhaps the most famous polymath here, but there are many others: Henry Lieberman invented garbage collection in programming languages, and is a pioneer in intelligent user interfaces. Rosalind Picard invented affective computing, and is a leader in autism theory and technology. Mitchel Resnick was involved in the creation of LOGO for kids, but is also a leader in inventing tools to the meet the information needs of information communities. Every PI here has deep expertise in at least a couple of fields.

3. You and yours only

In the Media Lab, there are no required courses, and no established curriculum. You can choose and pick any course offered through the Lab’s academic Program in Media Arts, other MIT departments, or even Harvard. Choosing what course to take is a bit like being a kid in a candy shop. My heuristic has always been this: take a course if it you need it for your research, and always attempt to write a conference-quality paper at the end of it. For me, this has resulted in some very long-lasting collaborations with other groups at the Lab.

4. Don't ever be away during IAP

The January Independent Activities Period, the month between the fall and spring semesters, is an excellent time to sharpen your creative acumen. You can experience anything from wine tasting to hummus-making courses. If you've never done pottery, or have had a desire to make your own glass sculptures, this is your time to try it. It almost always helps you to unleash your creative self when the spring semester gets underway.

5. Jump in and get involved

Last December, I was lucky enough to get involved in planning the end-of-year party. It was great getting involved in a Lab-wide event and I encourage you to jump in and do the same.

I still feel that same way about MIT as I felt the first day I got here. I'm inspired everyday when I walk to the Lab through the Infinite Corridor. From giving birth to modern-day information theory to discovering synthetic penicillin, this place has done so much for humanity. The coolest thing is that you are now part of this family. It's your turn to be unconventional.

Welcome to a most remarkable place!

Karthik Dinakar is a second year graduate student in the Software Agents group at the Media Lab.

The January Independent Activities Period, the month between the fall and spring semesters, is an excellent time to sharpen your creative acumen. You can experience anything from wine tasting to hummus-making courses. If you've never done pottery, or have had a desire to make your own glass sculptures, this is your time to try it. It almost always helps you to unleash your creative self when the spring semester gets underway.

5. Jump in and get involved

Last December, I was lucky enough to get involved in planning the end-of-year party. It was great getting involved in a Lab-wide event and I encourage you to jump in and do the same.

I still feel that same way about MIT as I felt the first day I got here. I'm inspired everyday when I walk to the Lab through the Infinite Corridor. From giving birth to modern-day information theory to discovering synthetic penicillin, this place has done so much for humanity. The coolest thing is that you are now part of this family. It's your turn to be unconventional.

Welcome to a most remarkable place!

Karthik Dinakar is a second year graduate student in the Software Agents group at the Media Lab.

Media Lab IP Commission

The Media Lab is considering a potential revision of its IP policy.

In order to ensure an in-depth analysis of the Lab’s relationship to IP, its past and current strategies, as well as evaluate possible future policies, the Lab is putting together a commission of both internal faculty/MIT researchers and external IP experts. The commission will be facilitated by a field researcher, Kate Darling, and convene periodically during the course of a year to review gathered insights, refine questions, and set the direction for the analysis. The field researcher will investigate the Lab’s historical and current relationship to IP, spend time in the Lab developing an understanding for the various innovation contexts and their relation to IP, collect input from all involved parties, and connect the gathered insights to theoretical work on the role of IP in networked innovation settings. On the basis of this field work, the commission will discuss suitable policies for the Lab and draft a report with recommendations.

Questions include (but are not limited to): The role of IP rights in the Lab’s sponsoring strategies; the importance of IP rights to the Lab itself, including their value to faculty and students; the relationship between the Lab’s policies and MIT’s IP policies; the general role of IP in the various fields of innovation that the Lab engages in; whether any aspects of the current policies are causing unnecessary hindrances; whether the policies can be modified to encourage innovation (both internally and in a more general, social context) and also reflect the ideological interests of the lab; and whether there are any IP-related initiatives and projects that the Lab could support or be engaged in that use IP in a creative way to solve problems or enhance innovation and invention.

The commission will be chaired by Lawrence Lessig and we hope to have a very broad range of view represented on the commission. We are in the process of compiling the list of candidates for the commission. We're also soliciting participation from students, faculty and staff to participate in the process. (Contact Kate if you're interested.) We'll also be working closely with our sponsors/members and other stakeholders.

I'm very excited about this initiative and also excited to that Kate Darling has started her work at the Media Lab this month. Please join me in welcoming Kate and please provide Kate and myself with any thoughts as we begin the process.

Thursday, September 1, 2011

New Students

Welcome to our new Media Arts and Sciences grad students. Here are as many of them as could be rounded up into one place at today's meet-and-greet gathering.

Welcome!

Welcome to the new MIT Media Lab blog.

This is one of the many exciting changes you’ll be seeing from the Lab over the next several months as we work to give more people the chance to participate in the very cool things going on here.

When I first started hanging out at the Lab, I noticed that while there was a lot happening, it felt slightly more like a container than a platform. There were lots of collaborations with outside groups–and many people travel out as well as visit in–but the awesome space that the Lab lives in, and the somewhat tricky issues around IP and confidentiality, have kept a lot of the great things going on at the Lab out of the public view.

I'd really like to have the Media Lab be more involved in the conversation that is the global Internet, and to invite everyone to participate in what we do. So in addition to initiating this blog, we will be streaming more of our talks, inviting more external people to our meetings, and exploring ways to adopt more permissive licenses for our content.

I officially come aboard as Lab director this month (yay!), so this just the very beginning of what I think will be an interesting journey and look forward to having everyone along for the ride.

This is a "soft launch" and we're looking for feedback. So please let us know if you have any ideas or suggestions on what else we should be doing or how we can improve what we already do.

Thanks!

This is one of the many exciting changes you’ll be seeing from the Lab over the next several months as we work to give more people the chance to participate in the very cool things going on here.

When I first started hanging out at the Lab, I noticed that while there was a lot happening, it felt slightly more like a container than a platform. There were lots of collaborations with outside groups–and many people travel out as well as visit in–but the awesome space that the Lab lives in, and the somewhat tricky issues around IP and confidentiality, have kept a lot of the great things going on at the Lab out of the public view.

I'd really like to have the Media Lab be more involved in the conversation that is the global Internet, and to invite everyone to participate in what we do. So in addition to initiating this blog, we will be streaming more of our talks, inviting more external people to our meetings, and exploring ways to adopt more permissive licenses for our content.

I officially come aboard as Lab director this month (yay!), so this just the very beginning of what I think will be an interesting journey and look forward to having everyone along for the ride.

This is a "soft launch" and we're looking for feedback. So please let us know if you have any ideas or suggestions on what else we should be doing or how we can improve what we already do.

Thanks!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)